Building a movement always challenges the status quo. Leaders must act, they must willingly risk the things they love. Unfortunately, many leaders are frozen by the lethargy of indecision. They fail to move.

I’m convinced that this indecision in leaders–the failure to act–rests in their perception of the powers opposing them. In building spiritual movements, they fail because they make what I call The McClellan Mistake:

They overestimate the strength of the enemy and underestimate their own strength.

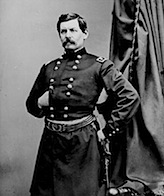

Early in the Civil War, after several discouraging defeats by Confederate forces, President Lincoln appointed General George McClellan to be senior commander of the Union Army of the Potomac. McClellan had won several small engagements in what is now West Virginia. McClellan, known as the Little Napoleon (the little describing his stature, the Napoleon describing his supposed military prowess but in reality describing the the size of his ego), wrote his wife after Lincoln’s appointment, “Finally, they have called upon me to save the Union.”

When General McClellan took command of Washington and the Army of the Potomac on 26th July, 1861, everyone had great expectations of him. He was a hero. Everyone expected great things from him. For a while it appeared they got them–he increased the defenses around Washington–not only making the capital safe, he made it “feel” safe.

His perceived success seems to have gone to his head. In another letter to his wife, he wrote “I seem to have become the power in the land” and “I could become dictator or anything else that might please me – but nothing of that kind would please me – therefore I won’t be Dictator. Admirable self denial!”

But McClellan’s mind was already being clouded by thoughts of the enemy opposing him. Again to his wife:[Confederate General] “Beauregard probably has 150,000 men – I cannot count more than 55,000. . .the enemy have 3 to 4 times my force.”

The reality was that Confederate Generals Johnston and Beauregard had to abandon plans for any offensive because they couldn’t muster 60,000 men between them. Having lost the initiative, McClellan settled in to continue to strengthen the Washington defenses.

Later in the Penisula Campaign, McClellan moved his army south to Fort Monroe. It was during this phase of the war that he constantly miscalculated not only the size of the Confederate army facing him, but also his own–constantly padding his estimates of the enemy to justify increases in his own. McClellan’s own estimates of the size of his own army varied from day to day, sometimes by as much as 17,000 men.

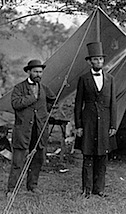

Allan Pinkerton (pictured to the right), at that time not much of a detective, supplied McClellan with estimates of the enemy’s strength. Pinkerton invariably padded the estimates of enemy strength and McClellan would pad it again. In Pinkerton’s estimates of Confederate troop strength submitted to McClellan, he exaggerated significantly. Often his estimates ran double the actual size of given Confederate forces. By routinely overstating the troop strengths reported by Pinkerton and his agents, McClellan allowed an inflation that worked to deter action by the Army of the Potomac, robbing it of a much-needed initiative.

Later, in September 1862, McClellan was back in Washington. That month, Confederate General Lee marched his army from Harper’s Ferry to Sharpsburg, knowing that that his Southern army was half the size of the Army of the Potomac, (40,000 men to 80,000). Besides, his men were tired, demoralized and looking like “scarecrows.” Enroute to Sharpsburg, a Confederate officer had also lost Lee’s entire battle movement plans which were found on 13th September and given to McClellan.

With all the odds on his side, McClellan should have won a tremendous victory on 17th September. McClellan had superior numbers, knew exactly where Lee would position his troops, but still produced a series of uncoordinated attacks that were very often late. McClellan inexplicably delayed a day before moving. The delay allowed Lee to obtain reinforcements and knowledge that his battle plans had become known by the enemy.

The subsequent Battle of Antietam was the bloodiest single day of fighting in the war and McClellan came out of it with only a draw, despite his vastly superior force. McClellan’s lack of coordination arose mostly from his estimate that that the Confederate army he faced was far larger than it really was. He thought that he was attacking at least 97,000 men, not the maximum of 40,000 that Lee had at his disposal.

And afterward, with Lee in a disadvantaged position, McClellan true to form did nothing. Once again he miscalculated the size of the remaining Confederate forces and decided he needed more reinforcements before he could do anything. Rather than a rigorous pursuit, McClellan stopped and waited for more men and supplies.

By now, people were becoming very impatient with McClellan. When he asked for more horses, Lincoln wrote to McClellan “Will you pardon me for asking what the horses of your army have done since the battle of Antietam that fatigues anything?”

Halleck said that “There is an immobility here that exceeds all that any man can conceive of. It requires the lever of Archimedes to move this inert mass.”

Lincoln eventually tired of McClellan’s failure to act. Lincoln found that McClellan had what he called “a case of the slows” i.e. being too afraid of losing to risk winning. McClellan was said by many to be deluded into always thinking he was outnumbered, regardless of what his intelligence told him. He was also said to have believed Lincoln and the government were conspiring to see him defeated and that the only way to overcome their plot was to move cautiously and rely only on his own intuition.

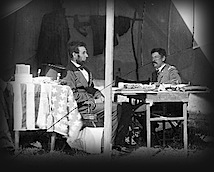

Once, while visiting the Army to encourage McClellan to move against Robert E. Lee, Lincoln had to join McClellan for an official photograph. While waiting, Lincoln wrote his wife Mary. “Mary dear, we are waiting to be seated for a photo. McClellan does not have any trouble with being seated. He likes to sit.”

For his part, McClellan continued the letter war, “The good of my country requires me to submit to all this from men whom I know to be greatly my inferior socially, intellectually and morally! There never was a truer epithet applied to a certain individual than that of the “Gorilla”. In addition to calling Lincoln a Gorilla, he complained about his other superiors: In a letter to his wife he wrote that “I have insisted that [Sec. of War] Stanton shall be removed & that [Cmdr in Chief] Halleck shall give way to me as Comdr in Chief. I will not serve under him – for he is an incompetent fool.”

That McClellan was academically very bright, personally brave, and a good organizer isn’t in doubt. Neither is the fact that he was a good unit commander and popular with the men under his command. He equipped his men with the best rifles, blankets and tents. They marched well and proudly under his leadership. He wrote his wife lots of letters and the Union Army grew in its espirt de corps. But McClellan would never send them into the fight.

He often explained his sluggishness to doing anything definite as “I’m waiting for the right time.” In Germany, strategist Field Marshall Count Helmuth Carl Bernard Von Moltke the elder (1800 – 1891) told his students that “No plan survives contact with the enemy.” That truth was something that McClellan should have known and guarded against, but this was another of his failings as a General. Once he’d conceived of a strategy and it had to be scrapped, McClellan would seem totally paralyzed. Frightened of failure and the consequences, McClellan failed to act.

As historians review the behavior of McClellan, they concluded two things:

“McClellan always (1) overestimated the size of the enemy by a factor of two and (2) underestimated the size of his own strength by the same factor.”

Again McClellan did many things right–he trained his army well, he procured the best equipment, he improved morale. His men loved him and he loved them. But Lincoln eventually fired McClellan because McClellan was unwilling to risk the thing he loved.

Later, to his surprise, the men who loved him in 1862 failed to support his presidential bid against Lincoln in 1864. For even the common soldier knew at the time that whether he liked it or not, he was in the army to fight. Not to sit.

Movements depend upon our willingness to walk in faith and to take Kingdom size risks. Faith engenders hope which counteracts fear. Despite the challenges we face, the Scriptures are clear— the forces with us are stronger than the forces opposing us. Jesus is becoming King in every place. Any movements we attempt to build will die from an unwillingness to risk. Of course, in the immediate fight, victory is never certain. But we’ll always fail to act if we make the McClellan Mistake of “overestimating the strength of the enemy and underestimating our own strength.”

So, when tempted to make The McClellan Mistake, remember these points:

- The Scripture’s most oft repeated command is “do not fear.”

- Fear of failure always makes you over-estimate the strength of the enemy and underestimate the strength of your forces.

- The moral arc of the universe always leans toward justice.– Martin Luther King, Jr.

- John the Apostle said, “Greater is he who is in you (and in your cause) than he who is in the world.”

- What you can do, or dream you can do, begin it; boldness has genius, power and magic in it.- Johann von Goethe

- Don’t blame others for your inaction.

- Reality is your friend. If great detectives wont give you the truth, find it out for yourself.

- Ego and self-esteem always intertwine with our ability to lead . . . there is always the tendency to put a spin on everything imaginable, while ignoring evidence to the contrary. We easily lose sight of what is really happening.-P. Senge