The Hard Road Toward Empathy

My counselor told me, “Jay, we need to work on empathy. With your narcissistic disorder, you might be able to display sympathy, but rarely empathy. Narcissism is really about a lack of empathy. You don’t have the ability to understand and share in the emotions of others.”

Ouch!

And I’m paying $110.00 an hour for this!

As he continued, the hole got deeper. “The narcissist has little room left to have genuine and sustained empathy toward others, for the world is all about him or her. So he or she can’t easily act in a way that requires sacrifice and humility.”

Could this get any worse? Apparently yes.

“Oh, and Jay, someone as old as you are can’t really change much. But, we can work on softening the extremes of your narcissism.”

“So it is possible to teach someone to be empathetic?” I asked my counselor.

“Well, not really,” he said.

I came back quickly. I had been to seminary and his answer challenged my understanding of the sanctification process.

“It seems to me that the Scriptures teach, that if I’m committed to becoming like Jesus, and step by step over time by His Spirit, I can become like Jesus. Doesn’t 2 Corinthians 3:18 say ‘as I behold the glory of the Lord, I am being transformed into the same image from one degree of glory to another?.'”

“Well, sort of,” he said, adding this truth.

“The Scriptures also teach that we will only be like him when we see him as he is (1 Jn 3:2). The perfection you seek Jay will only come fully when Jesus makes us and everything right. So right now, it’s about process, not product. If you were 30, we’d have more time. But since you’re 60, we’re stuck with working on developing the emotional connection you need to soften the edges of your narcissism. And, by the way, the fact that you’ve made this a theological discussion indicates that you are still in your head. We’ve got to get you out of your head and into your heart. You’re just a mind right now, but we can get you into a little bit more balance. You want to be a whole person, don’t you? Head, heart, hands, mind, soul, spirit, strength?

“Yes,” I said. “But if this doesn’t work, can I get my 110 dollars an hour back?”

Looking back now, the five years of counseling were worth ten times what I paid.

So, over the last ten years, I’ve been walking the hard road of cultivating empathy. Some progress, but I’ll have to wait for Jesus to return to complete the process.

Here’s a little of what I’ve been learning (and one example of how I see it played out during the Battle of Gettysburg.)

Empathy, as respected leadership scholars like Daniel Goleman and Simon Sinek argue, is a critical skill in leaders.

Here’s a little of what I’m learning (and how I see it played out during the Battle of Gettysburg.)

Empathy and Sympathy are not the same.

Sympathy makes you feel sorry or sad for those you lead, but empathy enables you to know the effect of your decisions and actions on the people you are trying to reach and to lead. And without empathy, it’s tough to build a team, elicit loyalty, nurture the next generation.

To do all these, you need to feel what others feel.

This is the tricky part of becoming more empathic.

This ability to understand another person’s experience, perspective and feelings, commonly described as the ability to put yourself in another person’s shoes, is called “vicarious introspection.” Jesus was so great at the “vicarious” stuff—weeping with Mary and Martha at Lazarus’ grave, weeping over Jerusalem, his gut wrenched that the crowds were harassed and helpless, and on the cross not holding their sin against them, crying out “My God, my God, why have you forsaken me.”

Our problem is as leaders we might have sympathy but so often we’re only feeling what we would feel like in their shoes, not how they feel in their shoes.

“Leaders with empathy,” states Daniel Goleman, “do more than sympathize with people around them: they use their knowledge to improve their companies in subtle, but important ways.” It is not that leaders agree with everyone’s views or try to please everybody. Rather, they “thoughtfully consider employees’ feelings – along with other factors – in the process of making intelligent decisions.”

Daniel Pink says “Empathy is the ability to imagine yourself in someone else’s position, to imagine what they are feeling, to understand what makes people tick, to create relationships and to be caring of others: all of which is very difficult to outsource or automate, and yet is increasingly important.”

To develop empathy, you have to dwell in the tears. You must exercise those feeling muscles.

Cultivating empathy is hard. For me, it started first in the mind, with the process of thinking more clearly. I needed to use my reasoning ability first to stop and think for a moment about the other person’s perspective and where they were coming from. I needed to acknowledge the other person’s thoughts, feelings, reactions, concerns, motives.

But it couldn’t stop there.

I needed to move to feeling and caring–from being in my head to moving into my heart.

My “110 dollar an hour” counselor gave me this priceless advice.

To cultivate more empathy, this is what I want you to do. Whenever you tear up, notice it. Stay in it. Don’t leave it for logic. Dwell in the tears for as long as you can. And before you let it go, ask God, “Lord, why am I tearing up?”

Part of the reason I love Gettysburg is I find myself walking these fields, learning the stories of these men, and tearing up. Over the years, I’ve used the idea of a thin place to describe those places on the battlefield where it seems like walking up to a low wall and peer over from things temporal into things eternal.

But there might be another application.

There are times in my life when I get to a low wall and peer over from my intellect into my emotions. Rather than walking away from that wall, my counselor was saying, stay at that wall. Peer over. See thru the veil. Dwell there.

Oh, and for several years, he had me stop reading non-fiction. Only in fiction, in novels, can you see that life is complex and people are complicated. Your non-fiction pre-occupation feeds your search for silver bullets. Silver bullets won’t kill the vampires of your narcissism. Life is not as simple as “Just do these 6 things and you’ll be like Jesus.”

To cultivate empathy, learn to listen. Develop the habit of deep and active listening.

One of the best books on leadership and discipleship I’ve read lately is The Listening Life: Embracing Attentiveness in a World of Distraction by Adam S. McHugh. It’s been so helpful. ( I’ll risk repeating what I wrote early in one of these letters.)

Leaders must learn to listen well – truly listen to people. We must listen with your ears, eyes and heart. Pay attention to others’ body language, to their tone of voice, to the hidden emotions behind what they are saying to you, and to the context.

The word “listen” appears in Scripture over fifteen hundred times, and the most frequently voiced complaint in the Bible is that the people don’t listen. Indeed, discipleship is a journey of ongoing listening, one in which true listening becomes the means for God to break up the “entrenched selfishness” of our own hearts. No wonder Jesus said, “he who has ears, let him hear.”

Listening to those we lead is also critical. Of course, Jesus set the example by listening widely (to the sick, the outcast, the despised), deeply (with probing questions and a heart for underlying need), and hospitably – fully present to the speaker.

McHugh advises us that to be like Jesus, we need to learn to “listening to,” rather than “listening for.”

This was particularly convicting.

In my information hoarding, I so often “listen for”— less like Jesus and more like a cross-examining attorney trying to catch any inconsistency or to hoard data.

But if I can learn to “listen to,” I’ll resist all my self-promoting, self-centered habits and keep the conversational arrow pointed unselfishly toward the other person.

One of the strongest chapters in McHugh’s book is his chapter on listening to people in pain. I so wished I’d understood earlier the empathy needed for listening to others in pain. Here’s what McHugh warns of:

“When we try to help someone in pain, we often end up saying or doing things, subconsciously, to assuage our own anxiety. Let’s be honest: we often want others to be okay so we can feel okay. We want them to feel better and move on so our lives can return to normal. We try to control the conversation as a way of compensating for our anxiety. Our approach to people in pain can amount to self-therapy.”

Instructively, McHugh tells us that we do not listen to others in pain to fix their situation (our default). But we need to practice empathy by “going down into the pit with them, weeping with them, letting our heart break with the heartbroken, waiting together for resurrection”.

Dietrich Bonhoeffer said it almost as strongly: “It must be a decisive rule of every Christian fellowship that each individual is prohibited from saying much that occurs to him. . . Many people are looking for an ear that will listen. They do not find it among Christians because these Christians are talking when they should be listening.”

The Listening Life imagines a world in which the usual pattern of listening is reversed, where leaders listen to followers, where the rich listen to the poor, and the insiders listen to outsiders (and professors listen to students) – not as part of a program or with a prescribed agenda, but one person at a time with listening as an end in itself.

Even God, McHugh said, is first a listener.

Let me close out this article with some additional thoughts about empathy.

- Don’t interrupt people. Don’t dismiss their concerns offhand. Don’t rush to give advice. Don’t change the subject. Allow people their moment.

- Use people’s names.

- Be fully present when you are with people. Don’t look at your phone.

- Smile at people.

- Encourage others to speak up in meetings, particularly the quiet ones.

- Give recognition and praise. Pay attention to what people are doing and catch them doing the right things.

- Take a personal interest in people. Show people that you care; mobilize your curiosity about others. Ask them questions about their hobbies, their challenges, their families, their aspirations.

- (Oh, and for me, be more like Laurie).

P.S. Here’s a great summary of the Emotional Intelligence we need as leaders.

The Hunt – Hancock Controversy

At the beginning of our walk across the ground of Pickett’s Charge, we discuss in some detail the actions of the Union artillery and its response to the Confederate cannonade that began around 1 pm on July 3rd, 1863.

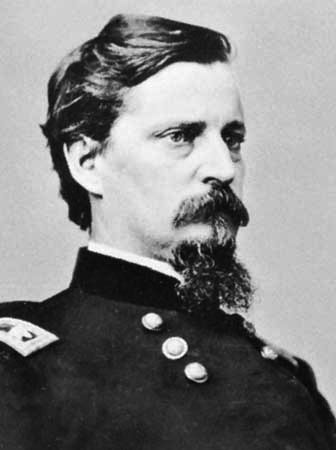

When the 170 guns opened up on the Union positions around the Copse of Trees on Cemetery Ridge, Major General Winfield Scott Hancock who commanded the men along that line ordered the Union artillery to respond.

The Union artillery, however, was under the direct command Brig. Gen. Henry Jackson Hunt, who had commanded the artillery to conserve their ammunition. A controversy erupted between the two generals, the language of which was not recorded.

One Union soldier admitted that Hancock occasionally let loose, “a stream of profanity which one expected from a drunken sailor, but not a gentleman….” Despite his temperament, Hancock always remained in control and performed his best when the situation seemed bleakest.

A fellow officer later recalled:

Of his peculiar qualities on the field of battle, I can say that his personal bearing and appearance gave confidence and enthusiasm to his men, and perhaps no soldier during the war contributed so much of personal effect in action as did General Hancock. In the friendly circle his eye was warm and genial, but in hour of battle it became intensely cold, and had immense power on those around him…. In General Hancock…the nervous, the moral, and the mental systems were all harmoniously stimulated [by combat] and…he was therefore at his very best on the field of battle.

A sharp disagreement occurred between Hunt and Hancock about the proper way to respond to the Confederate bombardment.

As the commander of the infantry along Cemetery Ridge, General Hancock insisted that the enemy’s fire should be stoutly returned on account of the moral effect on the infantry.…”

One of his aides wrote later that Hancock was most concerned about “…the loss of morale in the infantry…that might have resulted from allowing them to be scourged, at will, by the hostile artillery…. Every soldier knows how trying and often how demoralizing it is to endure artillery without reply…. [Hancock had] that intimate knowledge of the temper of troops which should qualify him…to judge what was required to keep them in heart and courage under the Confederate cannonade at Gettysburg, and to bring them up to the final struggle, prepared in spirit to meet the fearful ordeal of Longstreet’s charge.”

As Hancock told one of Hunt’s artillery commanders to fire, Hancock said “my troops cannot stand this cannonade and will not stand it if it is not replied to” and ordered Lt Col McGilvery to open fire at once.

Being only a lieutenant colonel, McGilvery reluctantly ordered his batteries to open fire. Being satisfied, Hancock then rode away. But McGilvery quickly countermanded his orders, as he described in his official report: “After the discharge of a few rounds, I ordered the fire to cease and the men to be covered.”

Most scholars of the battlefield believe that Hunt was right in preserving ammunition for the Confederate infantry assault. As the Commander of Artillery, he could afford to be more objective, less concerned for the feelings of the infantry

Hancock could not be so disconnected, for he felt perhaps what his men felt there on the line. Hancock possessed empathy as an infantry commander. His concern was for the morale of his men. He put himself vicariously into their shoes as they waited. As a result, he helped his men “find the courage to endure the pelting of the pitiless gale.”

Strategically, Hancock was probably wrong. But tactically, Hancock was right.

In matters of the heart and emotions, as my counselor reminded me, nothing is perfectly clear.

To learn empathy, you won’t find the silver bullet decisions your mind likes.

Life is too complex.

People are too complicated.