Lyrics

The Ballad of Johnny Shiloh

These fields are haunted – by men of glory

whose voices whisper on the wind

There hearts undaunted – they tell a story

of courage to the bloody end

Some fight for Liberty – some for the color of skin

but most just fight for each other

Beautiful tragedy – where the veil is thin

but “why do men fight who were born to be brothers?”

Shiloh play your drum, help us dance in the pain

Sing that song you just wrote bout the 20th Main

Lift your flask, make a toast to Jesus, country and Kin

Tomorrow will come soon enough, but tonight we still live

So Shiloh play that song again

The smoke has lifted – the rain has come

Its time to go home and be known

Sovereignly scripted – generations to come

Will hear of “great sacrifice shown”

So many died – but never forgotten

If you listen you can hear the sounds

Heroes lie, inside every coffin

Gettysburg you are hallowed ground

-Andrew Landers

Story

The Ballad of Johnny Shiloh

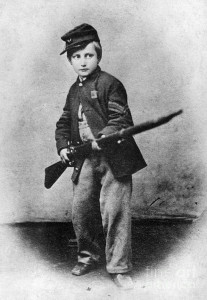

In 1861, John Lincoln Clem ran from his Newark Ohio home at age 9 to fight with the Union Army, eventually joining the 22nd Michigan as mascot and drummer boy.

Popular legend suggests that Clem took part in the battle of Shiloh, nearly losing his life when a shell fragment crashed through his drum, knocking him unconscious. Comrades found him, giving him the nickname “Johnny Shiloh.”

While historical evidence suggests he couldn’t have fought at Shiloh, John Clem certainly fought at the Battle of Chickamauga—even wielding a musket trimmed to his size to shoot a Confederate colonel who had demanded his surrender. After Chickamauga, this “Drummer Boy of Chickamauga” was promoted to Musician and Lance Sergeant at 12, the youngest solider to be a noncommissioned officer in the US Army.

The next month, Confederate calvary captured Clem in Georgia while serving with the 22nd Michigan guarding a train. They confiscated his uniform, including his cap which had three bullet holes in it. Confederate newspapers used his age and celebrity status to disparage the Union for “sending their babes out to fight us.” Included in a prisoner exchange, Clem returned to the Army of Cumberland and was wounded in combat twice during the war.

Discharged in September 1864, he returned to the army in December 1871. Appointed a second lieutenant by President Ulysses S. Grant, he served until 1915 when at mandatory retirement he was promoted to the rank of major general. When his first wife died in 1899, he married Bessie Sullivan, the daughter of a Confederate veteran. When he married her, Clem claimed his was “the most united American” alive. The Drummer Boy of Shiloh, certainly of Chickamauga, and other battlefields died on May 13, 1937.

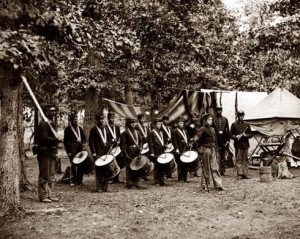

In these lyrics, Andrew imagined a drummer boy at Gettysburg like Johnny Shiloh. Drummer boys as well as other regimental musicians marched with the men into the Battle of Gettysburg, beating their drums to keep them together, playing songs to rally the hearts of soldiers facing battle or in the aftermath honoring the sacrifices they made.

The 20th Maine musicians were playing on Little Round Top on July 2nd, until finally ordered by Chamberlain to assist the surgeons.

Robert E. Lee once remarked that “without music, there would be no army.” It was said the music was the equivalent of “a thousand men” on one’s side. A reporter for The New York Herald wrote in 1862: “All history proves that music is as indispensable to warfare as money; and money has been called the sinews of war. But Music is the soul of Mars . . .”

In his classic book, Lincoln and the Music of the Civil War, Kenneth A. Bernard writes: “In camp and hospital they sang — sentimental songs and ballads, comic songs and patriotic numbers….The songs were better than rations or medicine.” By Bernard’s count, “…during the first year [of the war] alone, an estimated two thousand compositions were produced, and by the end of the war more music had been created, played, and sung than during all our other wars combined. More of the music of the era has endured than from any other period in our history.”

And fair the form of music shines, That bright, celestial creature, Who still, ‘mid war’s embattled lines, Gave this one touch of Nature. — John Rueben Thompson’s poem “Music in the Camp.”

In this album, Andrew Landers is showing us how the love of song can transcend political and philosophical divides—uniting a community, a church, a parachurch, a business, even a country. For the leader, music in any of today’s arenas doesn’t just help pass the time.

As Andrew writes: “If you listen you can hear the sounds” — for music entertains and comforts, it brings back memories of our homes and our families, it strengthens the bonds between comrades, it forms new bonds, it even creates new identities.

Great leaders recognize the power of this one touch of Nature.

The Drummer Boy of Shiloh by Will S. Hays

Role of Drummers in Battle: In the noise and confusion of battle, it was often impossible to hear the officers’ orders, so each order was given a series of drumbeats to represent it.

Both soldiers and drummers had to learn which drumroll meant “meet here” and which meant “attack now” and which meant “retreat” and all the other commands of battlefield and camp.

The most exciting drum call was “the long roll,” which was the signal to attack. The drummer would just beat-beat-beat — and every other drummer in hearing distance would beat-beat-beat — until all that could be heard was an overwhelming thunder pushing the army forward.

–Source: Washington Post