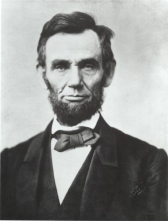

I’ve enjoyed reading lots about Abraham Lincoln this year. I’ve been wanting to work out some principles of movement leadership based on his life– here are some initial impressions and challenges:

1. Become an autodidact. Almost all biographers use the word “autodidact” to describe Lincoln. Sadly I had to look it up. To be an ‘autodidact’ is to be self-taught. Lincoln never had the advantages of a thorough public education or the opportunity to learn from private tutors. From an early age, he took responsibility for his own learning. Perhaps motivated by the memorized lines of Thomas Gray’s Elegy of a Country Churchyard, Lincoln refused to let his rural disadvantages “suppress his noble rage,” believing that even “in his neglected spot” he might have a “heart pregnant with celestial fire” or “hands, that the rod of empire might have swayed, Or waked to ecstasy the living lyre.”

To be an autodidact, we must assume responsibility for our own development. Typically, our organization (business, church, or parachurch) requires or provides training needed for the job we have to do. Unfortunately, job-specific training rarely ignites the “noble rage and celestial fire in the hands and hearts” (and minds) of employees or volunteers. Ultimately, what the organization needs most in its staff is not “generic job training” but the rage and fire that occurs only in “autodidacts.” Become an autodidact.

2. Be magnanimous. Lincoln refused to wear his feelings on this sleeves. Doris Kearns Goodwin, in her masterful work, A Team of Rivals, shows over and over how Lincoln lived above the tit for tat fray of political positioning. Lincoln kept his eye on the prize, enduring and overlooking whatever personal indignities came his way. He was, as one biographer stated, “a magnanimous soul.” In one famous incident, Lincoln was snubbed by General George McClellan, the commander of the Union Army of the Potomac. One Saturday afternoon, McClellan kept Lincoln and Secretary of State Seward waiting for hours in his parlor while he took a nap. Later, as Lincoln was returning to the White House, having failed to get his appointed general to speak to him, his aide John Hay suggested that McClellan be held accountable for such disrespectful treatment of a president. Lincoln commented, “Now, now John, if McClellan will only give me victories, I’ll gladly hold his horse for him.”

3. Learn to weave words. Originally, the word “text” comes from the Greek root teks which means to weave. Text thus suggests “textile” — a fabric woven of many strands. Just as linen or cloth can be woven into something useful, enduring and beautiful, text or words can be woven to achieve the same ends. Lincoln was a master weaver of words. One of the last presidents to do his own speech writing, Lincoln knew how to knit words–few speeches match the beauty and flow of the Gettysburg Address and of his 2nd Inaugural Address. He was called the Mark Twain of Presidents.

Lincoln wrote primarily to be heard. He crafted his speeches as much for the ear as for the eye. Though as one reads his speeches, one still senses the brilliance behind simple, clear, colorful phrases whose sounds echo in the ear. Listen for example to the prose-poetry of the last lines of the 2nd Inaugural speech:

With malice toward none; with charity for all; with firmness in the right, as God gives us to see the right, let us strive on to finish the work we are in; to bind up the nation’s wounds; to care for him who shall have borne the battle, and for his widow, and his orphan—to do all which may achieve and cherish a just, and a lasting peace, among ourselves, and with all nations.

4. Call others to do something great. Few of us went thru school without memorizing the Gettysburg Address, probably the most well-known and loved speech in American history. It taps into those God-ingrained desires to live for things beyond ourselves–by honoring those before us who paid the last full measure of devotion and by challenging us to complete the tasks ahead–that “good things” may long endure upon the earth. As the 2nd Inaugural Address also shows, Lincoln had a unique ability to call out a commitment to the shared values of his audiences.

Leaders can choose to speak at the various “P” levels listed below. Unfortunately, we sometimes believe that enforcing polices, procedures and practices will help align followers and achieve organizational goals. Lincoln knew that leaders call people to something great and to do so, a leader must speak above the line—at the level of philosophy, purpose, mission, vision and values. To lead movements, we must do the same.

Bruce Larson recorded the following story about Lincoln in his book, What God Wants to Know,

Lincoln often slipped into the Wednesday-night service at New York Presbyterian Church where Dr. Gurley was the pastor. In order not to disrupt things, he would listen from the privacy of the pastor’s study which adjoined the sanctuary. A young aide usually came along and on one particular night he asked Lincoln how he liked the sermon. “i thought it was well thought through, powerfully delivered, and very eloquent” was the reply. “Then you thought it was a great sermon?” the young man continued. “No,” said Lincoln, “it failed. It failed because Dr. Gurley did not ask us to do something great.”

5. Lead from a conscious conception of the flow of time from past to present to future. Lincoln’s leadership (as well as his speeches) seemed structured by an historical/existential/eschatological flow. In other words, he led from a sense of “what was right and wrong” about the past, from “what could be true in the future” while retaining an unrelenting commitment to “act in the present.” You see it in the Gettysburg Address, for example.

The Past: Four score and seven years ago, our fathers brought forth this nation…

The Present: Now, we are engaged in a great civil war . . . It is for us the living, rather, to be dedicated here to the unfinished work . . . for us to be here dedicated to the great task remaining before us . .

The Future: — that this nation, under God, shall have a new birth of freedom–and the government of the people, by the people, for the people, shall not perish from the earth.

Offended by the injustices of slavery (“if slavery isn’t wrong, nothing is”–Lincoln) in the past, Lincoln also believed that America could find the better angels of its nature by tough, committed magnanimous leadership in the present — constructing a new and better nation for the future. That future hope was worth any sacrifice.

Leaders of movements that “change the world” also lead from this historical/existential/eschatological sense of the flow of time. That’s part of the reason they can call people to do great things (always envisioned in a new more glorious future), while wrestling with the weight of the past through strong, future-oriented exertions in the present.

Trackbacks/Pingbacks